WINNER #APWA2021

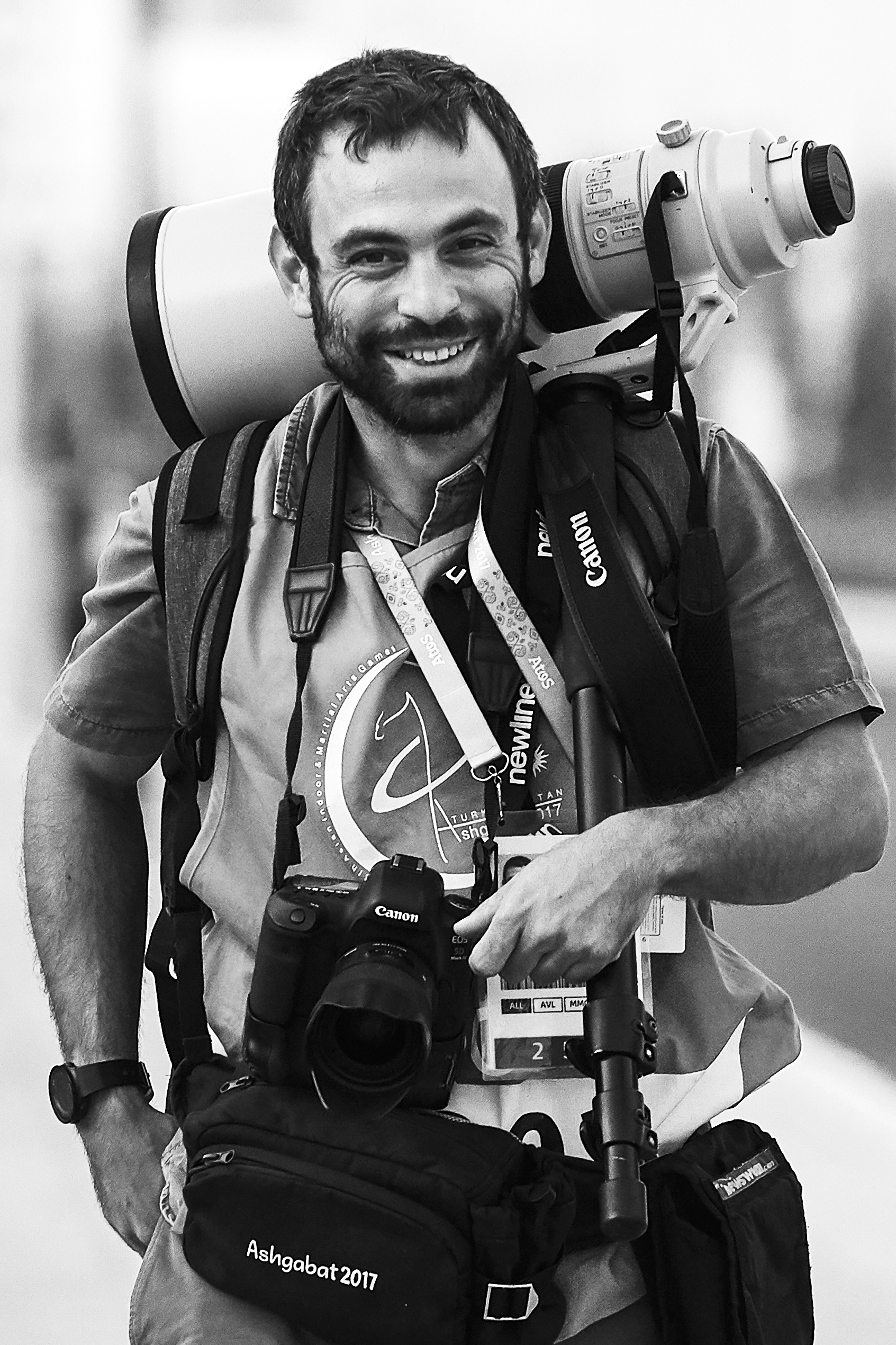

Dimitris Tosidis

Dimitris Tosidis was born in 1986 in Thessaloniki, Greece, where he lives. He studied in the Fine Arts College/Film Department of Aristotle University Thessaloniki and at UDK Berlin and he is attending the MA Risk Communication and Crisis Journalism course of Aristotle University Thessaloniki. He works as a photojournalist in Athens News Agency (ANA-MPA) and as a stringer in EPA ,and contributes regularly to Deutsche Welle and XINHUA. He focuses mainly on political/social issues, culture, sports/extreme sports and visual storytelling. He has been awarded multiple times for his work, most significantly with the Migration Media Award in 2017 and 2018 for his work on the refugee crisis in the Balkan area.

Diava, nomadic pastoralism in mountainous Northern Greece

Pastoral Farming, is a centuries old practice kept alive in the crisis stricken Greece. High in the mountains of Northern Greece a farming practice that belongs in previous centuries still takes place. This practice –or technique called Diava (in Greek means moving by feet)– which can be tracked down in centuries is the yearly rural migration of shepherds and their flocks between summer and winter pastures and from isolated highlands to warmer lowlands. Throughout time and spaces such movements have been at the core of cultural and social composition of mountainous farming communities while they have contributed to shaping and developing the landscape of the areas they took place. Practiced mostly by the Greece’s indigenous groups such as the Vlachs and Sarakatsans, pastoral farming used to be the country’s main practice until the 1960s and 1970s when new farming technologies started emerging. Recently, it became part of the UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage. Nowadays, very few families keep moving by feet without using any mean of transportation to keep their flock in high altitudes during summer and after move more than 200 km to go back to their winter destination which is in Thessaly region, Central Greece. This is not only a traditional and cultural action but also an ecological and environmental friendly practice which maintains the human presence in one of the most remote mountainous areas in Balkans and EU.

Physical distancing may be a primarily photographic function, however its transformation into social distancing, turned the photographic medium into an active part of biopolitics that deviated from the previously socially and physically “healthy”, creating the need for new “normalities” and forcing the city centre into a process of desertification, excluding any presence as potentially pathogenic –or carrying a previous, now pathological, normality.

Some mornings, to wait for Syngrou Avenue or the National Road to empty – either in order to cross them or to photograph the new normality – was something that in the pre-Covid era would not have even been possible to imagine.

ICUs have become our point of reference, not only as places of patient transport, but also as places of claiming what is necessary for the public health. However, they also became the model for how our personal spaces should be and how we should exist within them.

The dystopia of a possible and sometimes expected emergency, became a material reality and was experienced not in shared bunkers, where groups of people gather together to save themselves, but in millions of separate bunkers into which each private space was transformed.

Runner Up

Angelos Tzortzinis

Angelos Tzortzinis is a documentary photographer. He was born in Athens, where he finished his studies at the Leica Academy of Creative Photography. Angelos’s work has been recognised with several awards such as Best Wire Photographer by Time Magazine 2015, Magnum Foundation, UNICEF Photo of the Year 2020, POYi, Sony award, World Press Photo, Visa Pour l’Image among others. Since 2007 he works as freelancer in Athens.

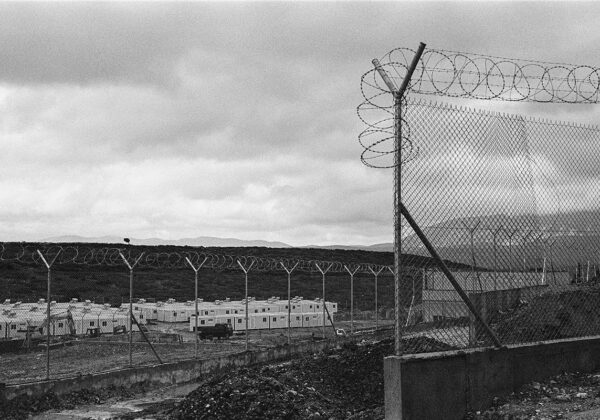

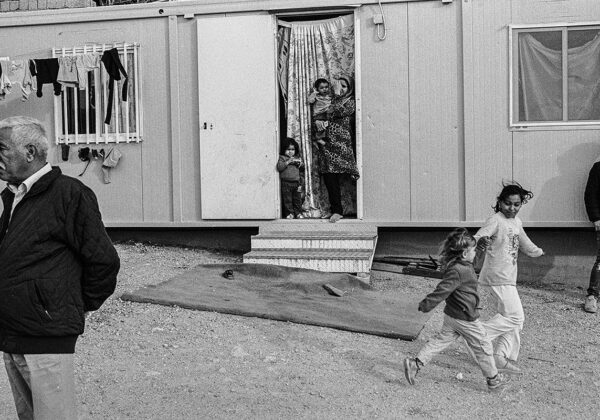

Trapped in Greece

I have been working on the migration issue for the last 8 years. This project researches the human and social adaptability. Tens of thousands of people fleeing war and poverty-stricken homelands have become stranded in Greece since the height of Europe’s refugee crisis in 2016. According to an UNHCR report in March 2016, more than one million people, mostly refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, had crossed into Greece since the beginning of 2015. As Balkan and European countries north of Greece began closing their borders to incoming migrants, more than 90,000 people were left trapped in Greece, in camps or on the streets. Moria Reception and Identification Center on the island of Lesbos, in the eastern Aegean, was the largest refugee camp in Europe, until it burned down in a fire in September 2020. By the summer of 2020, approximately 20,000 people were living in a camp built to accommodate 3,000. Residents complained of rain, cold, illness, lack of food and safety, unsanitary toilets, and water shortages.The fire, which broke out on the 9th of September, almost completely destroyed the camp. The Greek government said that the fires were started deliberately by migrants protesting that the camp had been put in lockdown as the result of a COVID-19 outbreak. On the nearby island of Samos, at the end of 2019, almost 8,000 refugees were living on a former military base that had been built to keep 650. Islanders held regular protests demanding the transfer of facilities to the mainland, and camp residents protested against their living conditions. This project was shot on Samos and Lesbos, and in refugee camps around Greece.

Petros Giannakouris

Petros Giannakouris is an award-winning Greek photojournalist. He is an Associated Press staff photographer based in Athens. For several years he has been documenting his county’s financial crisis, and among others, the refugee flow into Europe. Petros was born in 1974 and obtained a degree in photography from the College of Applied Photography in Athens. He has worked since 1995 for several newspapers and local news agencies, before joining the Associated Pressin 2003. He has documented an array of major stories in Greece, as well as international assignments including stories in Egypt, Jordan, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Albania, Turkey and Brazil, the war in Iraq (2007-2009), and the aftermath of the Israel-Hezbollah war in Lebanon in 2006. He has also covered major international sporting events including the Olympic Games. Giannakouris’s work has received numerous international awards, including: the PX3 Prix De La Photographie in 2011, the APME News Photos Award in 2012, the China International Photo Contest on 2013, the Picture of the Year on 2015, and on 2016 the NPPA Best of Photojournalism, the Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar and the National Press Photographers Association Awards.

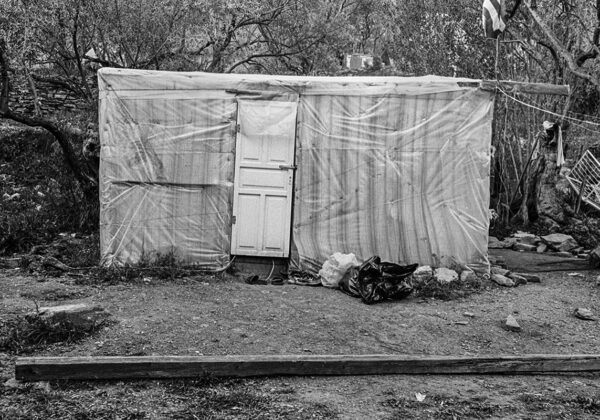

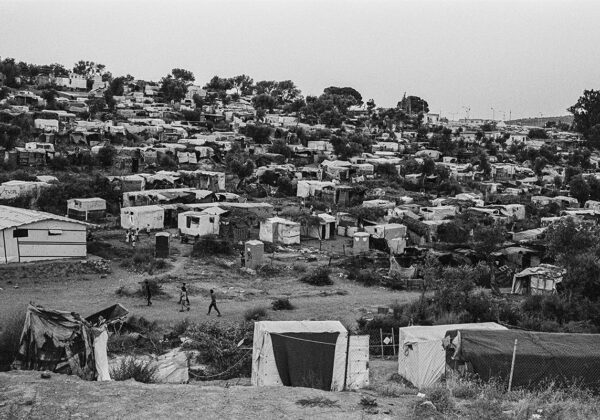

Moria, The End

Moria . The Moria refugee camp was never far from crisis. Created in 2013, before a massive influx of migrants five years ago, Greece’s largest refugee facility quickly exceeded capacity, spilling into surrounding olive groves on the island of Lesbos. With its squalid living conditions, frequent protests, and tension with local communities who saw their livelihoods disputed, Moria became a symbol of the impasse facing the European Union, unable to address the volatile migration issue with a policy accepted by all of its member states. The camp’s life ended as it began, in drama: Successive fires that started before dawn on the 9th of September, devastating the site and making 12,000 inhabitants homeless during a COVD-19 lockdown. Lesbos was again faced with a humanitarian crisis on a scale not seen since 2015, as families slept outdoors, most on the side of a highway near the gutted camp. Protests quickly broke out as many migrants sought to travel to Greek mainland and onto Europe, while authorities feared they might lose control of the spread of the pandemic. The crisis was eventually contained with a heavy deployment of police, a swift payout of European Union emergency aid, and the use of the army to build a tent city with a capacity of 10,000. The government says that what remains at Moria will be demolished, while its former inhabitants prepare to spend the winter in tents.